#

Myths & Misconceptions

The following section covers a few myths and misconceptions that are popular, and whether or not they have any validity.

#

More than Frequency Response?

The first thing to consider is whether or not FR is the only measurement that should be looked at, as EQ and the guide are based on the concept of FR being the dominant aspect of sound quality. In fact, the EQ guide works on the premise of IEMs being minimum phase systems for which the FR can be changed using minimum phase filters (used in most EQ software). The following sub sections cover different measurement types and their importance when assessing sound quality and EQ.

#

Distortion/Nonlinearity

The most obvious measurement to look at is distortion/nonlinearity. In the case of IEMs which are low excursion transducers, nonlinearity is mostly characterized by harmonic distortion (HD), and therefore any increase in other distortion metrics will be reflected in HD. It is therefore common to see measurements of total harmonic distortion (THD) when distortion figures are provided along with the tested SPL level. Indeed, as the SPL output of an IEM increases, so does distortion; when using EQ, the preamp will reduce the digital volume, but most will also increase the volume a bit to counter the preamp. Therefore, any time a positive gain filter is used in an EQ, the distortion in the affected region will increase.

What is not common is the inclusion of psychacoustic models such as masking. Therefore, most distortion measurements will be shown with two options: the first presented as "raw" data with no indication for how humans will perceive it, and the second with a generalized rule of thumb concerning distortion audibility. In both cases, the technical data is presented without much consideration for the human perceptual system. However, in most cases, distortion will not be perceptually significant with IEMs, and will not be audible even with extensive EQ. It is therefore unecessary to consider nonlinearity as being a big factor when using EQ.

#

Transients, Speed, & Responsiveness

A transient is often explained as being a short duration, single instance sound, such as the pop of a balloon or a gunshot. These are usually displayed in the time domain; instead of having frequencies on the x-axis, it is instead time.

The most common method way of seeing the transient response of IEMs (and other transducers) is by measuring the impulse response (IR) indirectly. Modern methods use different inputs and processing, but are analogous to feeding a single impulse into the IEM. The obtained output shows the response of the IEM over time. This single impulse contains all frequencies at the same amplitude, after which a Fourier transform of the IR is used to separate the frequencies and the corresponding amplitude of each frequency, which changed due to the FR of the IEM. In fact, FR measurements are all done by first finding the IR of the IEM, then doing the Fourier transform of it to obtain the FR.

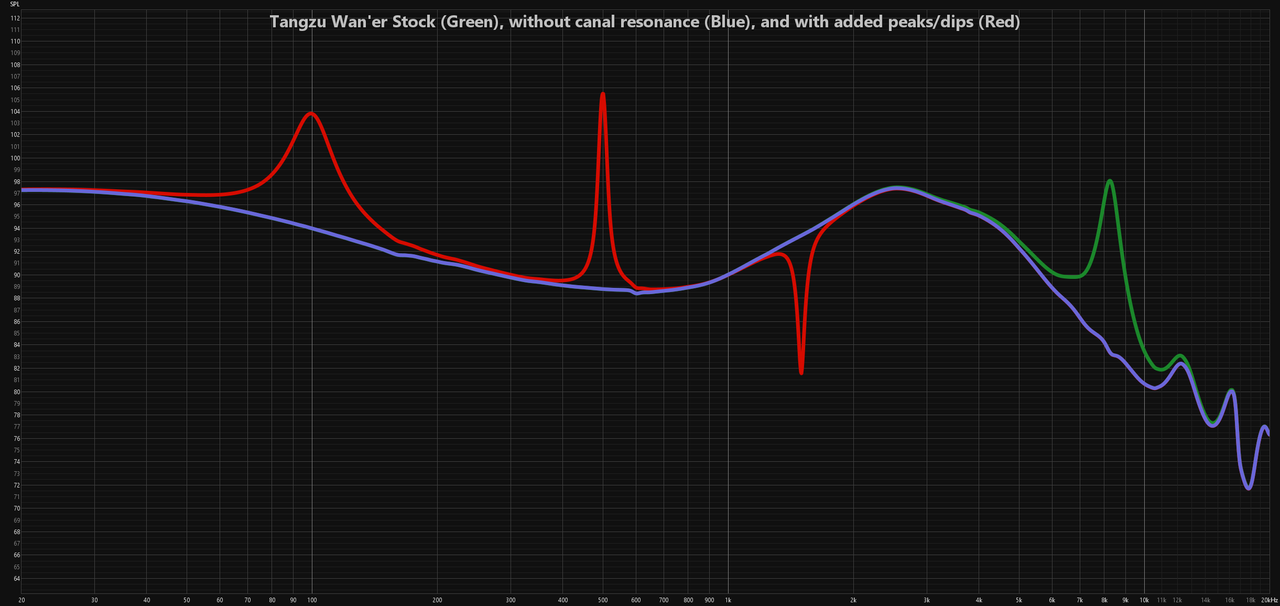

Below is a demonstration of the link between FR and IR (and other measurements) shown with two IEMs; both were measured, and one was re-measured using EQ to approximate the other IEM within reason (+/- 0.5 dB). By using EQ, or any method of changing the FR, there is a corresponding change in the IR and other measurements. These are causally linked, and therefore contain the same information. However, these alternative measurements are not helpful when trying to correlate it with what is being heard, and are not a valid method for characterizing "speed".

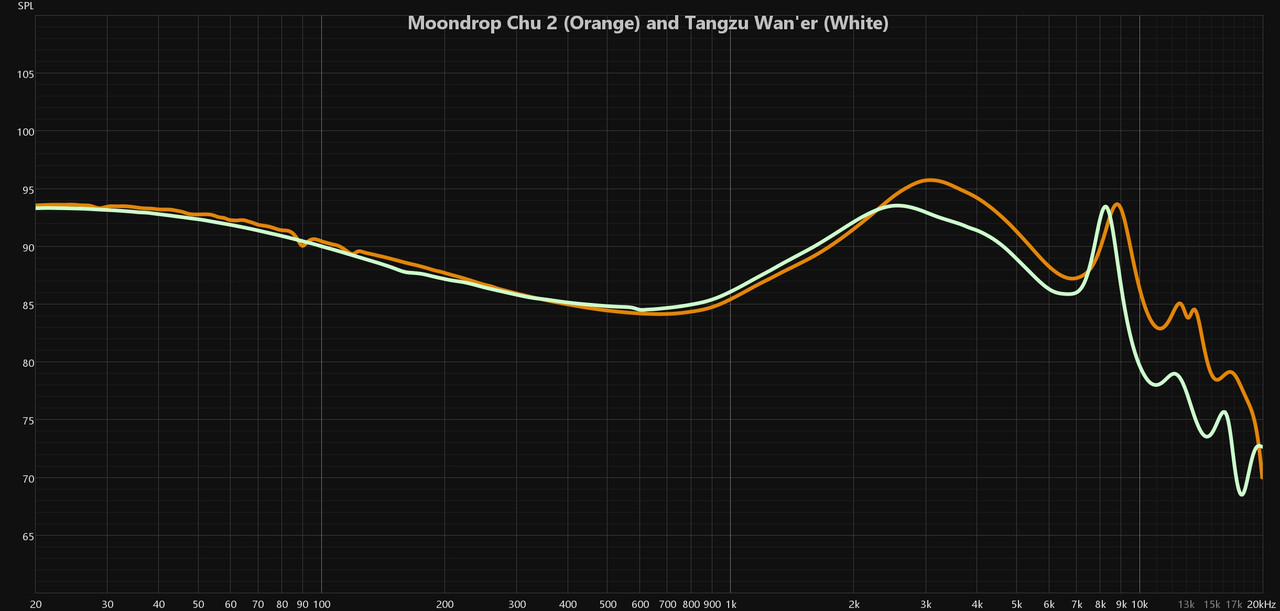

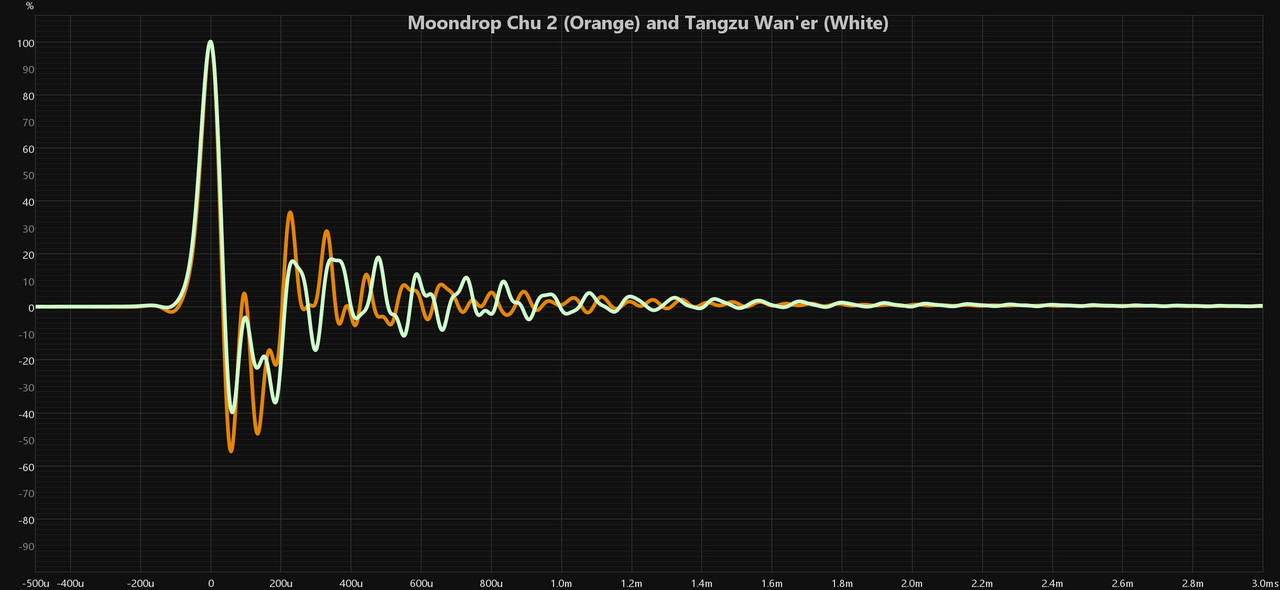

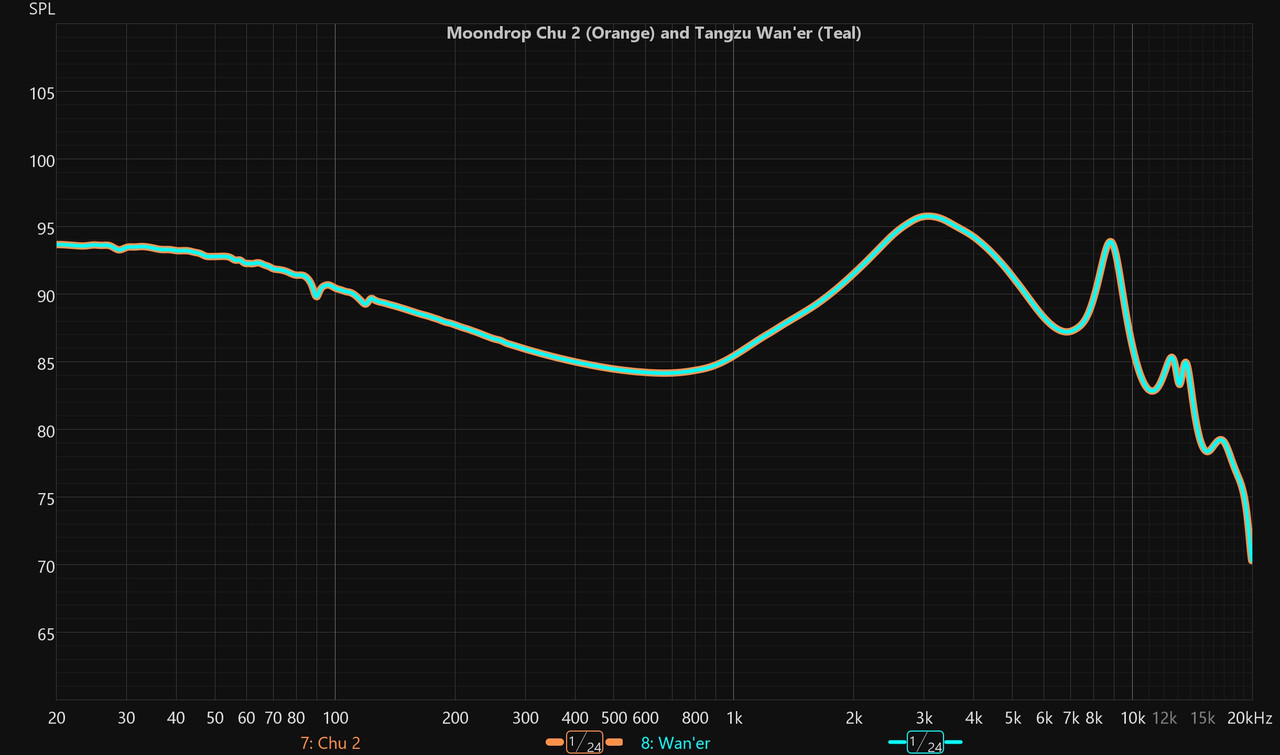

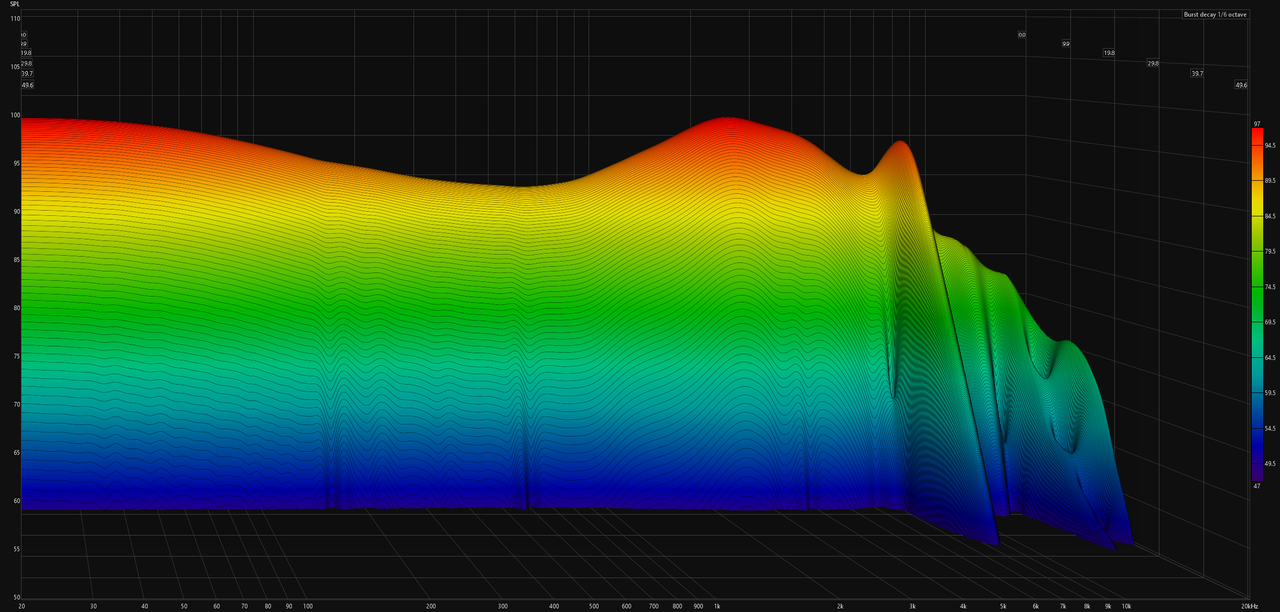

Below are the stock responses of the Moondrop Chu 2 and Tangzu Wan'er.

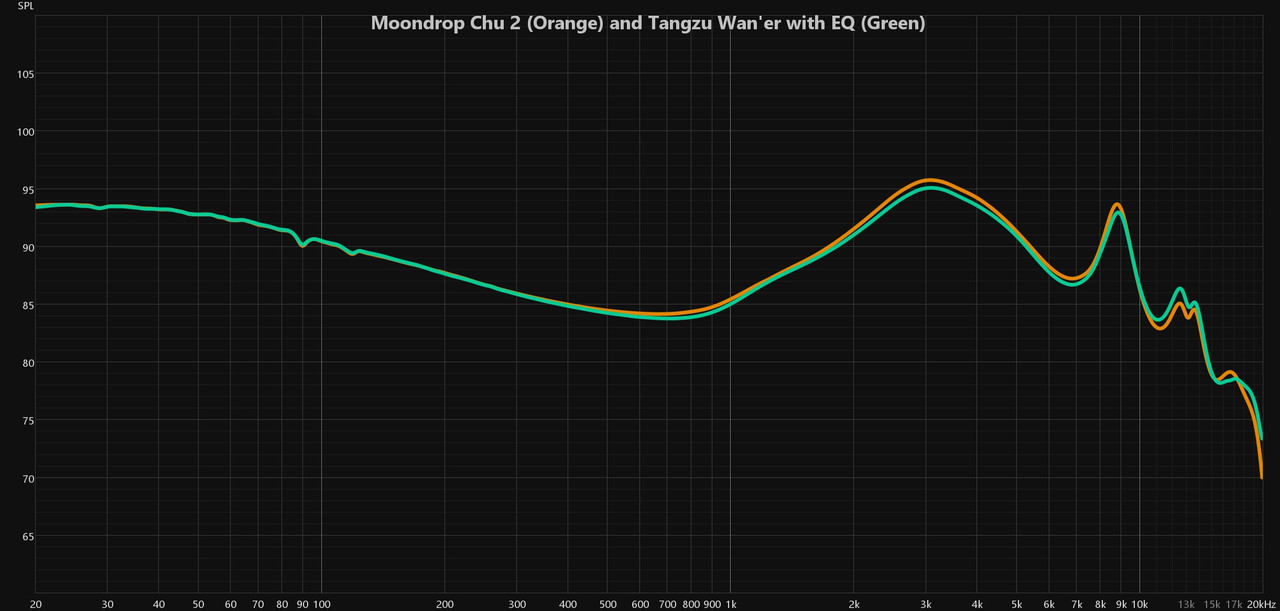

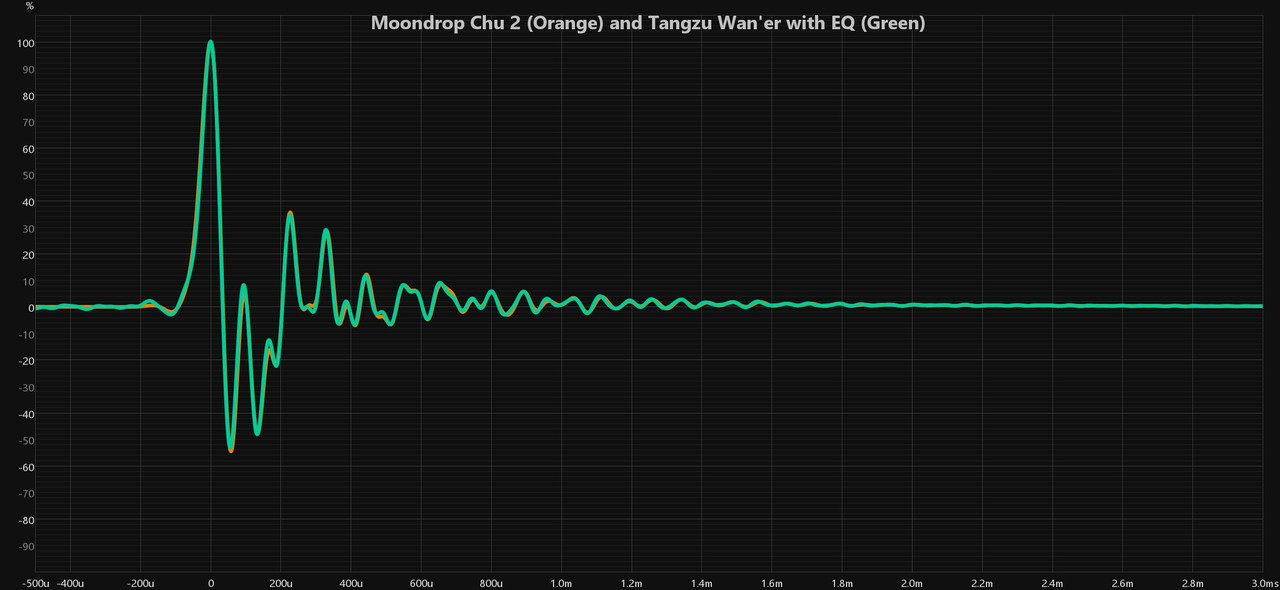

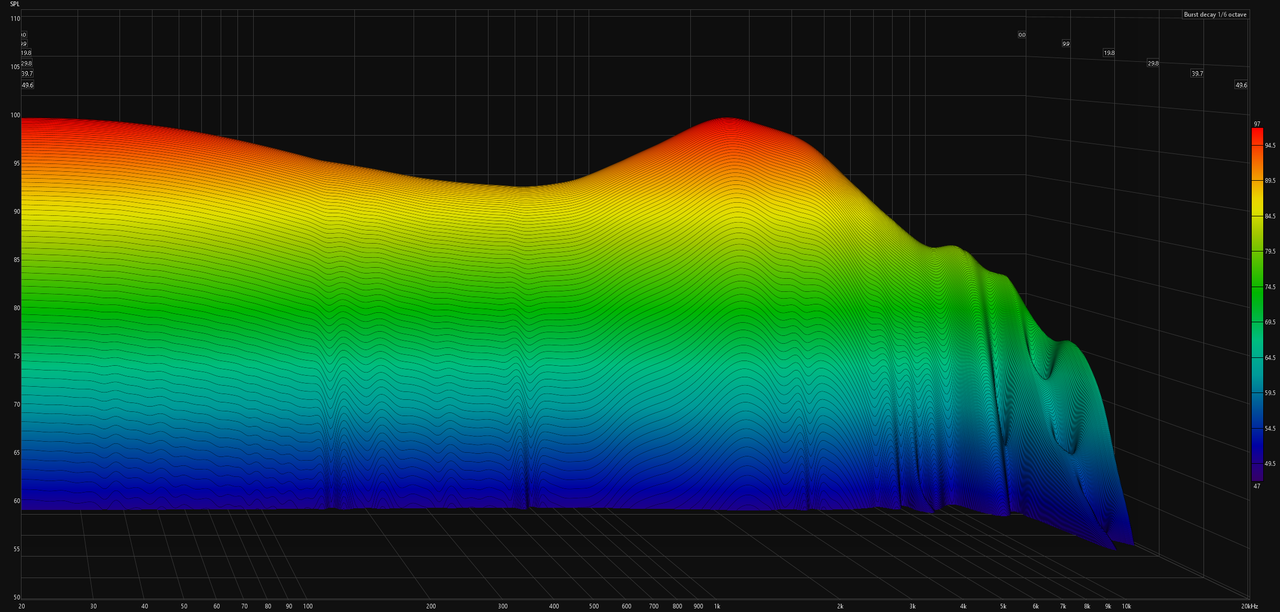

Below are the "fixed" responses of the Moondrop Chu 2 and Tangzu Wan'er, with the latter being changed to fit the former.

The small differences in the modified IRs are due to non-perfect matching of the two FRs. The modified FR graph even shows visible discrepancies between the two FRs, which then lead to different IRs. Additionally, these measurements were done without smoothing, which can cause very small artifacts in the FR which are hard to match. If they were smoothed, the task would be even easier.

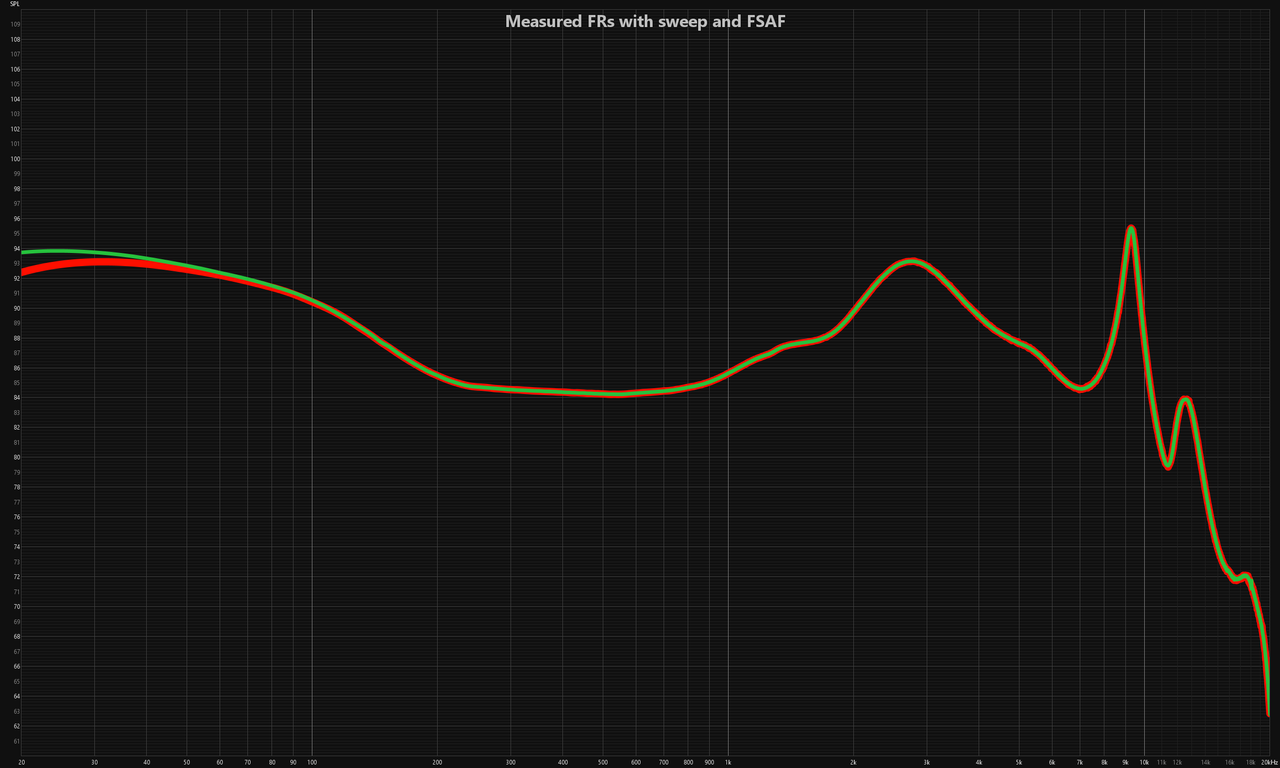

At the request of someone, below are images of perfectly matched FRs and IRs. As expected, there are no differences between the two; the lines overlap each other, making this a bit useless.

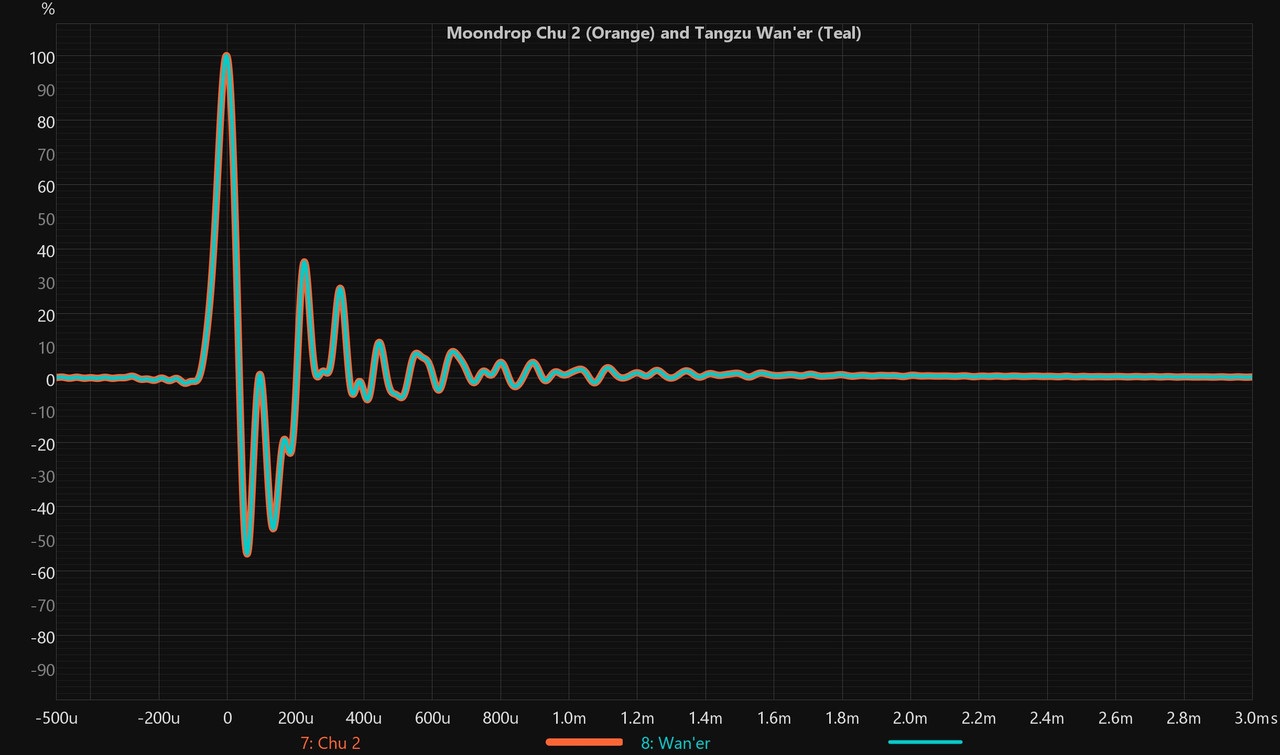

The video below shows a real-time square wave response (SWR) of an IEM. The three filters on the right are used to make the FR flat; in doing so, the response tends towards an expected square wave shape. Other filters are used to showcase the effect of FR on the response of the IEMs, showing that both SWR and FR are interlinked. However, FR is more comprehensive since SWR is worse to interpret and has to be measured at various frequencies.

To understand why both FR and SWR are linked, it is important to learn about what a square wave is. It is a function that has instantaneous transitions between a minimum and maximum amplitude occuring at a fixed frequency. When analyzed in the frequency domain, a square wave is simply the sum of multiple sine waves at various harmonics. Because IEMs are band limited (ie cannot play an infinite bandwidth), there is some ringing effect at the ends of the transitions. In the demonstration, the high shelf filter acts as damping: more damping (less higher frequencies) will undershoot the transition, seen as less ringing. For less damping (more high frequencies), there is overshoot and additional ringing.

There are other variables that can be discussed, but the image in the next tab shows the link between FR and SWR, and how the two are linked. However, proper understanding of FR will be more useful and consistent given the nature of SWR.

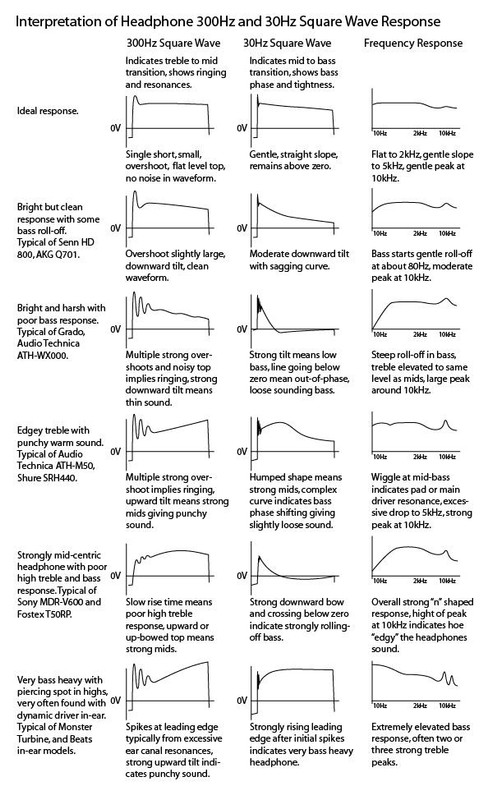

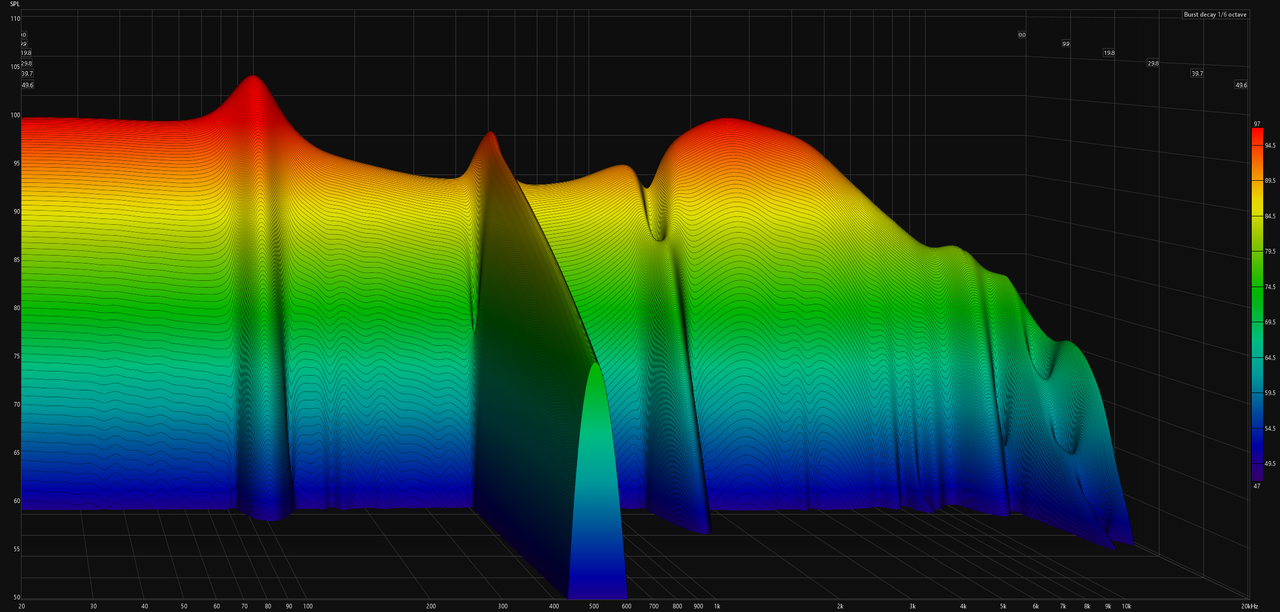

Below are three FRs of the Tangzu Wan'er, measured with EQ to remove and add peaks and dips.

The prominent resonance is situated around 8 kHz.

The prominent resonance at around 8 kHz is now gone.

The added peaks and dips appear as features here.

CSD, or waterfall plots, seem like the optimal way of displaying both frequency and time domain information. However, as discussed previously, time domain information, such as decay or resonance is causally linked to the FR by the minimum phase behavior of IEMs, as shown with the demonstration. Indeed, for minimum phase systems, any ringing and/or decay will reflect in amplitude in the FR: when these issues are fixed, so are the displayed ringing/decay features in waterfall plots.

Additionally, these plots can vary a lot based on the analysis parameters, and are ultimately unreliable methods of visualization that obfuscate the same information seen in FR.

#

Tuning & Technicalities Dichotomy

Popularized by Crinacle and adopted by many, the tuning versus technicalities dichotomy has become the most common way of thinking about sound quality with relation to IEMs (and headphones). The prevalence of measurements combined with uncertainty and mismatch with perception has resulted in a split between "easy to explain" aspects, grouped under tuning for and in consequence FR, and "hard to correlate" aspects, grouped under technicalities. The latter is of importance, since it is often thought of as being separate from tuning and FR, when that is not the case; in fact, based on what has been discussed before, FR is the most important metric for predicting sound quality and dominates over every other one. Much of what is labeled technical is merely tuning under another name, colored by expectation and subject to interpretation. The frequency response remains the most comprehensive and reliable indicator of what is heard.

The division has been further reinforced by the rise of EQ, which allows competent transducers to be shaped into nearly any response: in turn, tuning becomes a matter of taste, while technicalities are assumed to reflect the underlying quality of the driver, unalterable. If EQ can replicate one IEM’s frequency response using another, and if that response fully defines the sound, then what remains to distinguish technical performance? As detailed previously, FR defines, in most cases, the totality of audible output. No other measurable metric can be used to explain technicalities as being separate from FR. Therefore, it is better to think of technicalities as perceptual consequences of tonal balance and tuning quirks. When listeners point to an IEM having better technicalities despite "identical" FRs, they are often responding to uncontrolled variables, such as differences in insertion depth, ear geometry, HRTF, unit variation, isolation, or even expectations.

For technicalities to become something to consider as separate from FR, there are a few steps to take from the academic and industry side.

- The first is to define the terms used under the technicalities umbrella in ways that are consistent with people's interpretation and perception.

- The second is to provide a theoretical framework under which testing and measurements can be done to quantify these terms.

- The third is to provide conclusive differences in the measured data for these variables between different IEMs

- The fourth is to demonstrate the audibility of such variables

- The fifth is to examine the statistical spread and correlation between these variables, IEMs, and preference

These five steps aim to not only examine technicalities as being separate from FR, but also to verify audbility and preference, both concepts that are assumed to exist and match perfectly in the hobby.

#

Test Signals vs Music

Another common misconception involves the test signal used for measurmeents. Indeed, many argue that the sine sweep that is used currently is not representative of real-life "complex" signals like music, with many frequencies at different amplitudes occuring at the same time to the point where IEMs will have varying levels of "accuracy".

Depending on the algorithm, different stimulus signal can be the input, whether it be noise, music, sine sweep, etc. The resulting FR will always be the same (sometimes with miniscule differences). White noise, which contains all frequencies at the same amplitude, is similar in concept to IR with its single impulse containing all frequencies at the same amplitude. Music can be thought of as a form of noise, with the caveat of music having an FR of its own which will have to be removed by the algorithm in order to only obtain the transfer function of the IEM and not of both.

Nowadays, measurements use an exponentially-swept sine signal as detailed by Angelo Farina, which allows the user to measure both linear and nonlinear behavior of IEMs (or other DUTs) in a short time. In REW, options for measuring with sweeps and noise are available; a real-time analyzer (RTA) function is also present, allowing the user to measure the real-time response of an IEM (works best with white noise; if using music, the average FR of the music has to be subtracted).

#

Driver Type & Configuration Differences

Similar to the tuning and technicalities dichotomy, there are also a lot of ideas and concepts related to the drivers themselves that have been created and perpetuated to explain various perceived sound characteristics, despite many of them being false.

Concepts such as speed and decay have been shown to relate directly to FR and are therefore not immutable properties of the drivers. Other factors such as driver size are either Thiele/Small parameters (TSP), or linked to them, and it is these parameters that ultimately influence both linear (FR) and nonlinear (distortion) behavior. These parameters are often discussed as being directly related to how sound is perceived, when they are instead parameters that are used for a desired system.

The same occurs with driver configurations, which are often used as an indicator of performance. These claims assume that the driver configuration determines how an IEM performs, but in reality, they are only meaningful because they influence the FR. An IEM with many drivers can sound bad compared to a single driver IEM not because it is inherently worse, but because its FR is less optimal. In this sense, driver configuration is a means, not an end, to a desired and targeted FR.