#

EQ refinement (****)

At this stage, EQ is a tool that with which you are intimately familiar with, FR graphs are readable, decipherable, and hopefully enough to explain your perception of sound, and preferences have been found and more-or-less perfected. While measurements will still be useful, listening critically will be the main way of knowing what to change.

EQ refinement in this context refers to large and complex changes in the treble response for optimal timbre accuracy, and also intentional deviations colorations to improve "intangibles/technicalities". It is assumed that you have access to a good "reference" loudspeaker setup. This phase is inherently very personalized, and will require considerably more experimentation, trial and error, and time. Note that the tips provided from here on out will be based on what has worked okay-ish for me. Feel free to ignore, or even go against what is written.

#

Measurements and misinterpretation

At this stage, it is important to be more nuanced when it comes to reading measurements. While certain factors such as insertion depth and unit variation were discussed, there are other somewhat more complex issues that make measurements not as ideal as they seem to be when it comes to representing individual sound perception.

#

HRTF and individual variation

The first main issue arises from HRTF differences between individuals. Starting from around 2kHz, the variation in HRTF becomes quite significant, and increases in magnitude proportionally with frequency. For example, looking at the SADIE II database of DFHRTF measurements done at the blocked ear canal, the patterns described previously can be seen clearly, where amplitude differences of up to 20 dB can be observed above 10 kHz (image on the left). Note that since the HRTF database was measured at the blocked ear canal, it does not include the canal transfer function and potential variations in the frequency range it affects; the variations are therefore even more pronounced and can go down as low ass 1 kHz. What this means is that even if IEMs produced the same FR at the eardrum of two separate people, their perception of the produced sound will be different (assuming said perception can be measured, quantified, and compared), despite having the same response at the eardrum - read more here. The image on the right shows open and blocked canal measurements of 40 HRTFs for a frontal source: while not directly comparable to the DFHRTF image from the SADIE II database, it does still show the very large deviations in HRTF above 1 kHz depending on the individual.

#

Measurement system accuracy

The second issue comes from the inherent differences in acoustic impedance between not only the measurement system and the listener, but also between different measurement system standards. While more details can be found in the Measurement rigs, curves, and preference targets section, it is worth summarizing the differences between the "711" (IEC 60318-4) and "5128" (ITU-T P.57/58 Type 4.3) measurement databases as they are the most prevalent right now. The "old" standard is the most commonly used standard, and has extensive data, while the new standard has a much lesser amount of data, but is more "accurate" then the former.

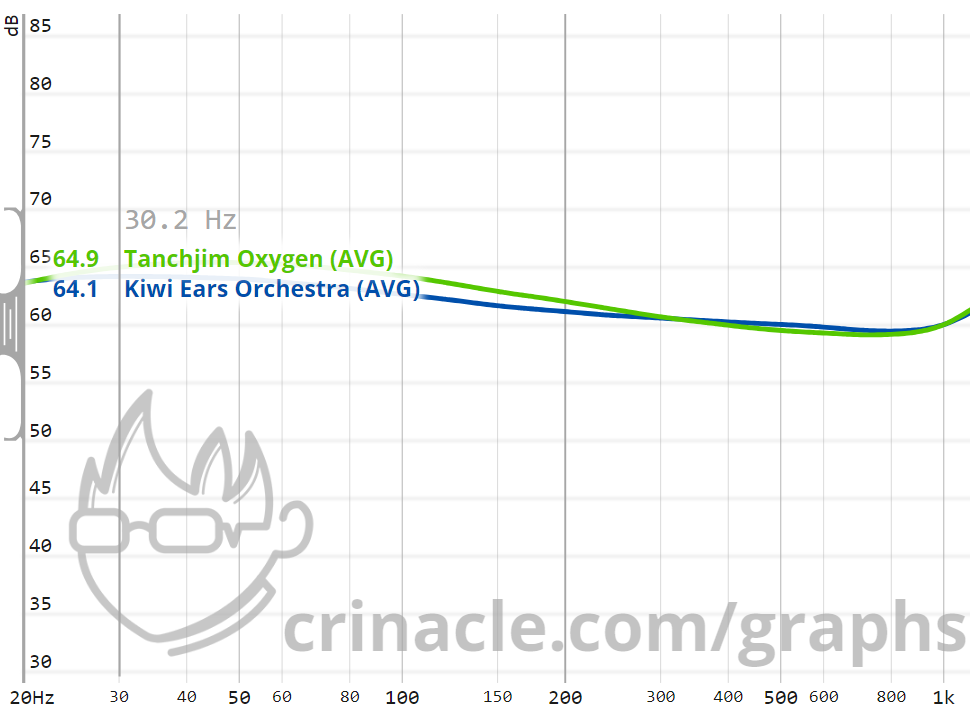

The differences between the both of them can be boiled down to a difference in acoustic impedance, with the newer standard being more accurate to the human population (ie matching the mean better). For expected changes when it comes to graphs, there are a three main places to look at: the bass region below ~150 Hz and above to 1 kHz, the frequency range between 1 kHz and 5 kHz, and the rest above 5 kHz. The former is very important, with 5128 measurements showing clear differences in bass. There are two main changes; the first one relates to overall bass level, where 711 measurements tend to overexaggerate amplitude below 150 Hz, and the second one relates to the relative difference between IEM models with different driver configuration, which explains the commonly talked about "BA bass" (see image below). These differences make the 5128 measurements generally more reliable when it comes to representing what a listener is hearing. As for the latter place, the increased accuracy is somewhat useful, although precautions have to be put in place. From 1 kHz to 5 kHz, the new standard adheres to the mean acoustic impedance better than the old one, although the differences don't seem to be noticeable and/or consistent. For the last region above 5 kHz, the newer standard is much better than the old one, but is not nearly as useful, since HRTF, insertion depth, and other factors result in wildly different responses away from the mean.

The image above includes a 711 and 5128 measurement of the Etymotic ER2XR with somewhat similar coupler resonances at around 13.5 kHz. All the differences mentioned previously are visible: the 5128 measurement has noticeably less bass and mid range compared to the 711 and relative to the rest of the FR, the more accurate acoustic impedance from 1-5 kHz doesn't seem to result in as substantial of changes, and the treble above 5 kHz looks drastically different despite the very close coupler resonance. It is important to note that direct comparisons are not valid, and that notions conceived for 711 measurements (eg bass to ear gain balance, bass levels relative to FR, etc) cannot be applied for 5128 measurements.

The two images above highlight the noticeable difference in leakage tolerance, the right being measurements done on the 5128, and the left the 711 (both normalized at 1 kHz). For high output acoustic impedance drivers (in this case the balanced armatures in the Orchestra), the difference in acoustic impedance plays a bigger role, and so the change in bass compared to an IEM with a relatively low output acoustic impedance (in this case the dynamic driver in the Oxygen) will be more pronounced on 5128 measurements compared to 711 ones. All of this is important to consider because 5128 measurements are done with an attached pinna which is much harder to have a proper seal with compared to 711 measurements which are taken with a bare coupler (ie a straight metal tube which allows for much better seal).

Unfortunately, most FR databases of IEMs are currently being done with the old standard, while ones done on the new standard are limited in scope. It is therefore important to understand the differences discussed previously, and how they can muddy the waters when it comes to reading FR measurements and correlating them with personal experience.

#

IEM and canal interactions

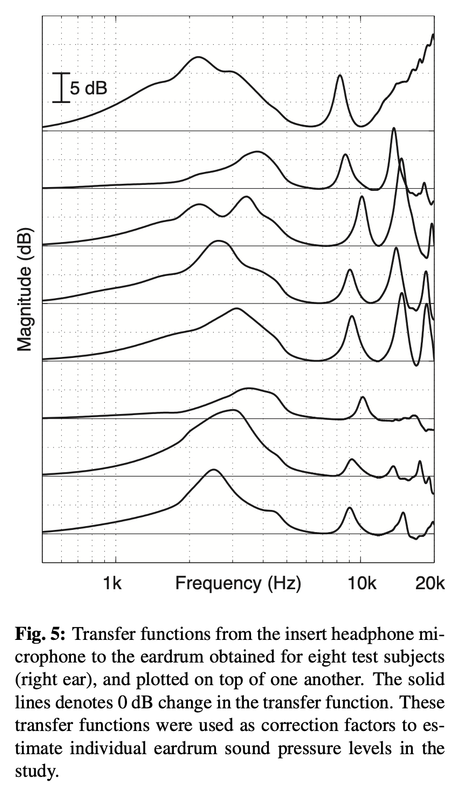

The third reason is related to how FR can vary depending on how an IEM couples and interacts with the ear canal and eardrum. When an IEM is inserted into the ear canal, the transfer function between the IEM and the eardrum can create meaningful peaks throughout the treble range, and for which the amplitude, location, Q, and number of peaks varies considerably with the individual, and depends on many factors, such as ear canal geometry. The images below show such potential transfer functions; notice the variance in terms of peak amplitude and Q. The canal transfer function is highly variable depending on the individual, and the peaks shown on measurements can also be a result of either insertion, driver resonances, or other factors, for which the transfer function will inevitably be masked or mixed with said variables. Furthermore, some IEMs employ forms of damping that try to mitigate such resonances. The interaction between the IEM and the canal of a person is therefore not shown accurately on 711 measurements, where canal geometry is not present, and even on 5128 measurements, the peaks in response will shift around depending on the individual.

Summary of measurement misinterpretation

- HRTF differences above 1 kHz will result in wildly different perception of sound

- Acoustic impedance differences and deviations of measurement systems from population averages means that measurement don't necessarily reflect what is being heard for an individual

- IEMs will cause treble changes which depend on personal anatomy, and are not easily identifiable in measurements

These reasons are why measurements take a back seat at this phase. Individual anatomy creates very large differences between perceived and measured response, so much so that using measurements without understanding such nuances can be detrimental. The main points to remember are the first and third ones; for the second point, points 1 and 3 are most probably bigger and more significant above 5 kHz. Change in acoustic impedances between 1 kHz to 5 kHz is relatively small and shouldn't matter much as long as measurements are used relative to your perception (not as an absolute metric), while the difference in acoustic impedance under 100 Hz is somewhat overshadowed by personal bass preference. It is therefore important to use measurements and compare them relative to what we personally hear, and to not be afraid to ignore or even "go against" them when they deviate too much.

#

Easy way out

There is a method that is considerably easier and arguably more accessible than what follows, but it does require 5128 measurements and will most likely provide less personalized results. While large scale preference targets as seen with Harman would be ideal, there are no current formal studies done with the 5128. Instead, the best option as of now (in my opinion) is using derived/calculated targets using population average measurements. More details are in the Rigs, Curves, & Targets section. A mix of the tips given previously can be used; see if the measurements correlate well with personal perception, then ignore or use the parts that match well.

#

Loudspeakers as a reference

Before going any further, having a reference loudspeaker setup is necessary; at the very least, having heard one is crucial. The reason is linked to how HRTF ties in with listening to IEMs: since IEMs bypass most of the ear as well as the rest of the body, they have to emulate those transfer functions. As such, IEMs and their tuners have to guess the correct HRTF (ie guess the correct ear gain level, location, and features).

For loudspeakers, the incoming sound is influenced by the listener's HRTF already, and therefore only the "raw" FR of the loudspeaker is considered. As mentioned in the Rigs, Curves, & Targets, IEMs and headphones should try to recreate similar timbre as heard with loudspeakers. Timbre in this case refers to overall tonal balance between bass, mid range, and treble, as well as conformity with your HRTF. Remember, the response at your eardrum from loudspeakers will have your own HRTF contributions, while IEMs can only guess, and often times, incorrectly.

It might seem logical to reason that because the brain applies the inverse of the HRTF to the incoming sound and therefore perceives sound from a loudspeaker as flat (since the HRTF contribution matches exactly to what the brain expects), using something like a tone generator and doing sine sweeps would be optimal. If the brain ultimately perceives the flat response of a loudspeaker, shouldn't we EQ the IEM's response to be perceived as flat as well? Wouldn't that mean that whatever HRTF contributions from the IEM have been removed and replaced with the correct response, resulting in perceived flatness?

Unfortunately, the human hearing mechanism is not a simple pressure detector. While the eardrum is one, the overall human hearing mechanism has to account for localization: HRTF aids in sound localization and so simply accounting for amplitude isn't enough for achieving accurate timbre. If loudspeakers and IEMs functioned the same in terms of sound localization, then the previous assumption would be true. However, IEMs and loudspeakers (or other localizable sound sources) are inherently different audio reproduction systems, and do not have the same "spatial rendering" features as loudspeakers.

Summary of loudspeakers

Loudspeakers, by design, create an eardrum response that has the correct HRTF contributions. The brain then goes through a localization process which transmits spatial perception through hearing. The brain then applies the inverse filters to the HRTF response as it expects; the resulting perceived sound is therefore flat/neutral with no coloration. In the end, two pieces of information are obtained: the spatial cues of the loudspeakers and room, and the spectral and tonal balance of the loudspeakers and room. For IEMs, both the HRTF contributions and localization process from listening with loudspeakers are incorrect and incompatible. Another method has to be used.

Loudspeakers are still useful because they are a reference point for accurate timbre as explained previously. The problem is that trying to compare timbre on both system is very difficult because of auditory memory, different spatial perception, isolation, etc. Despite these drawbacks, comparison between the two can still be useful, albeit very time demanding. The aim here should be to attain something as similar as possible, since the difference in sound field and perception will inevitably make IEMs have less accurate perceived timbre. Note that the following methodology can also be used to emulate other IEMs, although having both IEMs in hand is necessary.

Comparison between loudspeakers and IEMs for timbral accuracy

- Only compare IEMs to loudspeakers in the listening position

- A/B test as fast as possible. Blind A/B/X testing for preference is also recommended

- It is also possible to use headphones and measure/correct their response at the blocked canal and using those as the reference

- Examine overall tonal balance when comparing, mainly concentrating on the mid range and treble regions

- Adjust treble using broadband filters. Aim for a similar balance, paying attention to the overall treble level

- Use pink noise or music to compare timbre. Do not use sine sweeps or tone generators

- Adjust using fine filters. Eliminate differences, both peaks and dips, in perceived treble response

- Move on to the mid range when treble correction is done

- Adjust bass level to preference

HRTF or treble linearity

While replicating one's HRTF seems to be the optimal end goal based on the theory presented above, other studies have shown mixed results concerning personal vs general HRTF matching with relation to preference and localization. The idea of trying to match your HRTF will be kept for the rest of the guide and mentioned as perceived flatness, but it is important to note that a measured (ie not perceived) treble response could very well also be a good goal to aim for.

#

Treble changes

The previous rules were very general and provide very little guidance on how to actually finetune treble response, which is arguably the most important frequency range in that it influences everything else due to the nature of musical content and harmonics. The following steps are very crude, and while the end goal is to try and match the resulting FR to your expected HRTF as described previously, none of the steps outlined here will be accurate in any way; only preference and rough matching to loudspeaker timbre are considered.

The first step from before was to adjust the overall level of the treble, with either low Q peak filters or shelf filters. When the overall level has been adjusted, more precise changes can be done. At this stage, using pink noise is recommended over music as treble content will be consistently present at all times. It is important to do A/B testing when comparing loudspeaker and IEM perception at this stage and to not let yourself get accustomed to IEM presentation. Frequent resting is also recommended.

Fixing dips in the response is the hardest part, as dips are harder to detect than peaks. A good way to start would be to start at a relatively high frequency, and to add a sharp peak filter with a relatively moderate gain. Then, shift the filter by an increment of your choosing. For example, you could start at 5 kHz, with a filter of Q=5 and gain of 5 dB, and then use 300 Hz increments. Check to see if the boost is properly balanced out by the rest of the pink noise, and compare thoroughly with loudspeakers. Make sure that you take proper breaks to remove potential biases. It is particularly difficult to judge this change properly; a lot of times, these types of small boosts will be preferred on the sole basis of being perceived as bringing more "detail", hence why having a reference (ie loudspeakers) is so important.

By "sweeping" the frequency range this way, the chance of detecting a particular perceived dip should be much higher at the cost of being a very demanding, fatiguing, and time-consuming - with all the breaks and "brain resets" necessary for proper evaluation - task. Adjustments to both Q, increment, and gain should be examined and tested thoroughly in an iterative manner until the most optimal timbral accuracy is achieved. Subsequent testing (A/B/X or otherwise) between different EQ presets should also be performed while also taking into consideration rest, hearing fatigue, and brain burn-in.

The main issue with this method is the holistic nature of FR perception, and how the changes that were previously discussed do not consider it. For example, adjusting the bass as the last step - after everything in the treble has been corrected - might alter perception of treble and mid range; the same can be said about changes in the treble that induce perceptual changes in the bass or mid range bands. The whole methodology is therefore akin to a cat-and-mouse game, where constant changes require additional changes which require additional changes ad infinitum.

Two changes to the methodology can be made to mitigate the issue: adding more simultaneous variables (eg using two filters for the sweep method), or changing the parameters of the variable (eg changing the Q of the second filter, or using non-linear frequency increases for the filters). Unfortunately, there is no solution that I'm aware of that aims to tackle the issue and does so in an easy, simple, and efficient manner. This stage requires a lot of time and will most likely result in frustration and tiredness rather than a better EQ preset.

#

Intangibles and technicalities

"Intangibles", or "technicalities", are subjective terms used to describe certain characteristics of sound that an individual is perceiving that are not readily readable in FR measurements. Terms like "soundstage", "resolution", "dynamics", and "speed" are widely used, but there is no strict definition because they are based mainly on individual perception. While there seems to be a common consensus about what these terms mean, they are not remotely close to being consistent from one person to another, from one IEM to another, and from one moment to another. Therefore, there is no guarantee that anything that follows will result in better perceived technicalities, and it bears repeating that sound perception is deceptively fallible.

One relatively common perspective on these technicalities is that they are either "hidden" in FR graphs, or that they are subtle colorations of FR (large enough to be noticeable, yet small enough to not be tonally off-putting). The former explanation makes sense when considering all the reasons why measurements can be inaccurate, while the second one is plausible but would need some sort of testing to be certain.

For any following tips and tricks, use very small FR increases; while it was previously mentioned that human hearing is bad at detecting peaks and dips lower than 3 dB, this only applies to relatively high Q features. Most of the changes that should be applied should be started at very low amplitudes since the goal is to alter perception of technicalities while influencing overall tonal balance as little as possible.

#

Bass "quality"

Whether referencing "texture", "impact", or any other metric, bass quality is often presumed to be wholly unrelated to FR since attempts at improving it through EQ usually do not work. The problem comes down to measurement inaccuracies, as described previously, and to the holistic nature of FR. Furthermore, certain tracks/genres will emphasize or tone down bass levels, adding another variable to consider.

The most important factor to account for is leakage. It is not a binary system where there is either leakage or not; rather, depending on the canal entrance geometry and the ear tips being used, variable amounts of leakage are possible. Boosting bass to appropriate levels can sometimes feel wrong due to large amplitude filters, but is essential in improving bass quality perception.

- Bass transition to the lower mids at around 150-300 Hz is important depending on the wanted bass presentation. Making a clear distinction in that region can improve bass quality in terms of "speed" and "separation".

- Balance between sub bass and mid bass can be modified to increase "speed", "physicality", "dynamics", etc. Emphasized mid bass (eg decreasing everything below 50 Hz) can lead to a "punchier" and "tighter" sound. More sub bass can lead to better "rumble" and "presence", but can also muddy certain tracks

- Drums and other bass instruments with a lot of harmonic content can be perceptually altered by considering not only bass frequencies, but also higher frequencies; pay special attention to the 250-400 Hz range, and consider everything below 4 kHz. Kicks and bass synths can be more "dynamic" and "detailed" by increasing higher frequencies, and if needed, reducing fundamental frequency ranges

- Sub bass can be reduced to further emphasize "punch" and "dynamics". Use a high pass filter and check if bass improves by starting at 20 Hz and going up in small increments

#

Details and resolution

"Details" and "resolution" often refer to the overall perceived amount of sonic information that is being presented. For example, a "detailed" IEM might make certain elements in a track, like small filler percussions (eg subtle maracas), more noticeable, or it can increase harmonic information of a specific element (eg a violin sounding more "textured"). On a very basic level, resolution and detail are tied to relative high frequencies levels: common elements in music that are linked to detail include breaths, instrument textures, subtle percussions, and more for which high frequencies are responsible for a lot of the harmonic content in these elements.

The first part to consider is auditory masking, where large peaks can mask surrounding frequencies; having proper treble response is important, though the degree of adherence seems to vary. The second part is overall high frequency levels relative to the rest of the FR as well as relative to the specific element that is to be highlighted; for bass instruments, high frequency content will be in a different range than for something like vocals. The difficulty here lies in differentiating between actual tonal changes and perceived resolution.

Unfortunately, there aren't many specific tips that are useful because these aspects vary in terms of preference and perception depending on the individual. The only advice would be to use strategic broad changes to change detail perception for the wanted elements. , and boosts in higher frequency ranges (3-12 kHz) will usually result in increased detail perception; it is important to do small incremental changes as well as taking frequent breaks much like in the loudspeaker comparison method.

- Unfortunately, there aren't many specific tips that are useful because these aspects vary in terms of preference and perception depending on the individual. The only advice would be to use strategic broad changes to change detail perception for the wanted elements

- Dips in lower frequency ranges (250-400 Hz) can help certain elements to pop out with more "clarity" and "resolution", mainly vocals and some instruments. Boosts around 150 Hz can result in more "textured" bass

- Boosts in higher frequency ranges (3-12 kHz) will usually result in increased "details"

- it is important to do small incremental changes as well as taking frequent breaks much like in the loudspeaker comparison method

#

Separation, imaging, and soundstage

For both imaging and soundstage, proper compensation to your HRTF should result in somewhat accurate localization imparted by the music itself since the factors for proper sound localization are not in effect here (direct/indirect sound from space reflections, ILD, ITD, head movement, and spectral differences from HRTFs of "real" sounds). For separation, a proper balance of every part of the FR should be achieved by paying attention to "transition ranges"; the goal is to keep the overall levels of each instrument and track at appropriate levels. For example, mid bass shouldn't be too emphasized if mid range is to be preserved; in the case of mid bass having too much energy, masking of certain mid range elements can happen, as well as coloring instruments in said ranges.

These descriptors are arguably the most variable and inconsistent metrics when it comes to subjective impressions. There are however a few common tips that, at best, seem to somewhat work for some people. A few tricks employed in music production can also be handy here.

- Basic mixing techniques can be used here; overall loudness and balance of said loudness for specific instruments can impart a sense of "depth" and "separation"

- A dip at 1-2 kHz might impart a sense of "separation" and pushes vocals and other elements in a track "further away"

- High levels of high frequency information seems to be somewhat correlated with a more "spacious" presentation

- Bass is sometimes associated with a "closed in" feeling. Reducing it can increase "spaciousness" by reducing that feeling and by indirectly increasing treble